Our Plastic Brains & Ezra Pound's Dangerous Conversion*

- stephaniehawkins6

- Sep 30, 2025

- 5 min read

“Any judgement of MUSSOLINI will be in a measure an act of faith, it will depend on what you believe the man means, what you believe that he wants to accomplish.”

— Ezra Pound, Jefferson and/or Mussolini (1935).

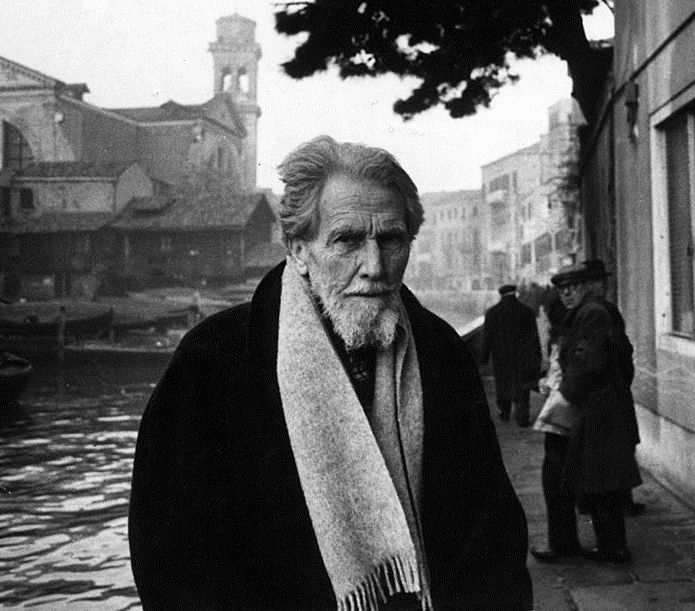

Poet Ezra Pound was a champion of the modernist literary movement, known for its clean, spare imagery and rejection of superficial ornamentation. How was it that the writer who advised poets in 1913 to “consider the way of the scientists rather than the way of an advertising agent for a new soap” turned to promoting fascism?

By the time of his 1945 arrest for treason, Pound had delivered more than 120 paid radio broadcasts for fascist Italy, as “an American,” in his words, on a mission to “save the Constitution” and warn against “usurers who destroy us.” Eighty years later, the FBI investigation known as “the Pound case” still contains urgent lessons for anyone who cares about democracy.

Those lessons begin with the discovery in the late nineteenth century by Harvard mind scientist William James: our brains are “plastic,” or malleable, meaning that by exercising our will we can develop habits that will, in time, alter our thinking. Such transformations, or conversions, as James observed in his Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) are universal to the human mental condition, and they can be gradual or sudden. With the right conditions, any profound experience, such as falling in love or committing oneself to a cause, can serve as a catalyst for conversion.

Conversion follows several distinct phases. First, a feeling of unease or acute internal conflict sets the stage. This is the state of mind James referred to as the “divided self” or the “sick soul” for whom conversion then brought about a “rebirth” into faith and dedication to a higher purpose. The fragmented, disoriented self finds wholeness and purpose, a resettling of identity, through a belief in something or someone perceived as fundamental and stabilizing. Pound and his generation who survived the First World War and who sought to shore up civilization’s ruins were primed for conversionary crisis. What made Pound’s particular conversion so dangerous was that his “rebirth” involved allegiance to one man, one system, one belief. Conversions are dangerous when they inhibit our mental adaptability—our capacity to question, or to doubt—by locking our thoughts into familiar, unalterable grooves.

Disconcertingly, such conversions can happen to any of us, regardless of our education or upbringing.

Mental Settling: The Lure of Simplicity

Dangerous conversions begin with devotion to a single person or system of belief that becomes the unifying source of identity. Pound came to believe that the “national mind” was racially determined and always threatened by some contaminating influx of an alien racial strain with its own mental qualities and tendencies. Pound’s incipient fascism had already emerged, in 1929, with his worship of art as a regenerative “force,” with the power to “affect one mass, in its relation … to another mass wholly differing, or in some notable way differing, from the first mass.” By 1931, Pound applied this understanding to the role of literature “in the state,” having to do “with the clarity and vigour of ‘any and every’ thought and opinion. It has to do with maintaining the very cleanliness of the tools, the health of the very matter of thought itself.” In his 1934 essay “The Teacher’s Mission,” Pound argues that “[t]he mental life of a nation is not man’s private property. The function of the teaching profession is to maintain the HEALTH OF THE NATIONAL MIND.” In Pound’s view, when one person acts, they act in concert with the national—that is, racial—mind. According to this thinking, individuals are never particular and unique. The epic narrative built around a heroic man, a social code, a force acting on the masses, a cleansing and purifying hygiene of race and nation: each of these elements speaks to Pound’s conversionary turn toward totalitarianism in the 1930s.

Pound’s particular kind of intelligence made him temperamentally unsuited to self-doubt or self-reflection. The “essence of fascism,” as Pound would tell his radio listeners, was “NOT to look for help anywhere outside yourself, and your immediate surroundings.” No other statement of Pound’s is so directly opposed to pluralism or democratic thought. No mere financial need drove Pound to espouse anti-Semitic conspiracy theories or to lavish praise on Mussolini and, later, on Hitler. Pound was a true believer, and his propaganda, as much as his predisposition to locate “genuine” culture in a distant, mythic past, provided the indispensable element of habit to reinforce, preserve, and insulate his beliefs. At the core of Pound’s fascist faith was an innate hostility toward democratic individualism and an equality of human beings based on the sacred possession of mind.

Salvation through “Soul Sickness”

The mental habits of unwavering ideological commitment, intellectual isolation, and a refusal to reckon with complexity form a kind of unholy trinity that undermines democracies across the globe. It’s far better to be one of William James’s “sick souls,” aware of the world’s agonizing multiplicity and endless churn, than a monist, fundamentalist, or fascist seeking to dominate or destroy anything abhorrent to the system of one man, one rule, one belief.

If Pound, in that light, serves as a case study in the mental processes that lead to authoritarian or totalitarian conversions, then an antidote of sorts can be found in the mental practices that James and his fellow modernist mind scientists advocated as a way of breaking through lies and disinformation. James urges us to assume responsibility and care for our own mental hygiene as the most powerful ethical act of all.

Pound is an extreme example of an all too commonplace phenomenon. Once one converts to a cause or a belief, it can be nearly impossible to alter course and restore mental flexibility. Other American literary modernists sought to cultivate our mental flexibility by innovating narrative and linguistic forms that would challenge our habits of perception, estranging us (and liberating us) from all that we take for granted. Modernist techniques such as stream-of-consciousness or fragmented perception bring us all face to face with our individual responsibility to test our beliefs against reality and against multiple other perspectives that may not be our own. Implicit in this aesthetic approach is an understanding of the human mind as a highly adaptable phenomenon, neither permanently rigid nor always vulnerable to dogma, but rather capable of self-reflection and self-correction.

By disrupting readers’ habits of perception so that they might become more self-aware participants in democratic self-governance at the level of public opinion, the literary modernists achieved a broader civic aim: they attune us to our own and others’ complexity. Beliefs, James argues, do not just happen; rather, they are made by countless daily actions and interactions with the many systems through which we as human beings move and breathe. Crucially, moreover, beliefs can be unmade. If we remain vigilantly attentive to our place within these systems, we will become aware of our internal divisions and of the various ways in which our lives touch each other through language, whether published or spoken, virtual or material. The writers I cover in the chapters of Manufacturing Dissent: William and Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Katherine Anne Porter, John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner and Jean Toomer, Zora Neale Hurston and Gertrude Stein, all chose soul sickness as a vital, if paradoxical, expression of mental health and civic dissent, one that requires conscious effort. In the process, they recall us to a humbling recognition of our interdependence with a fragile and finite network of others. If we understand the processes of thought and its complex neuroanatomy in the brain, we will be better equipped to take responsibility for, and recognize the limitations of, our beliefs, our choices, and our actions. This is the ethical path forward in a world in which the siren song of authoritarian ideology is once again finding many listeners all too willing to convert.

*published on Cambridge.org September 30, 2025 (https://cambridgeblog.org/2025/09/our-plastic-brains-ezra-pounds-dangerous-conversion/)

Comments